Etymology

The name « Dambe » derives from the Hausa word for « boxe », and appears in languages like Bole as Dembe.

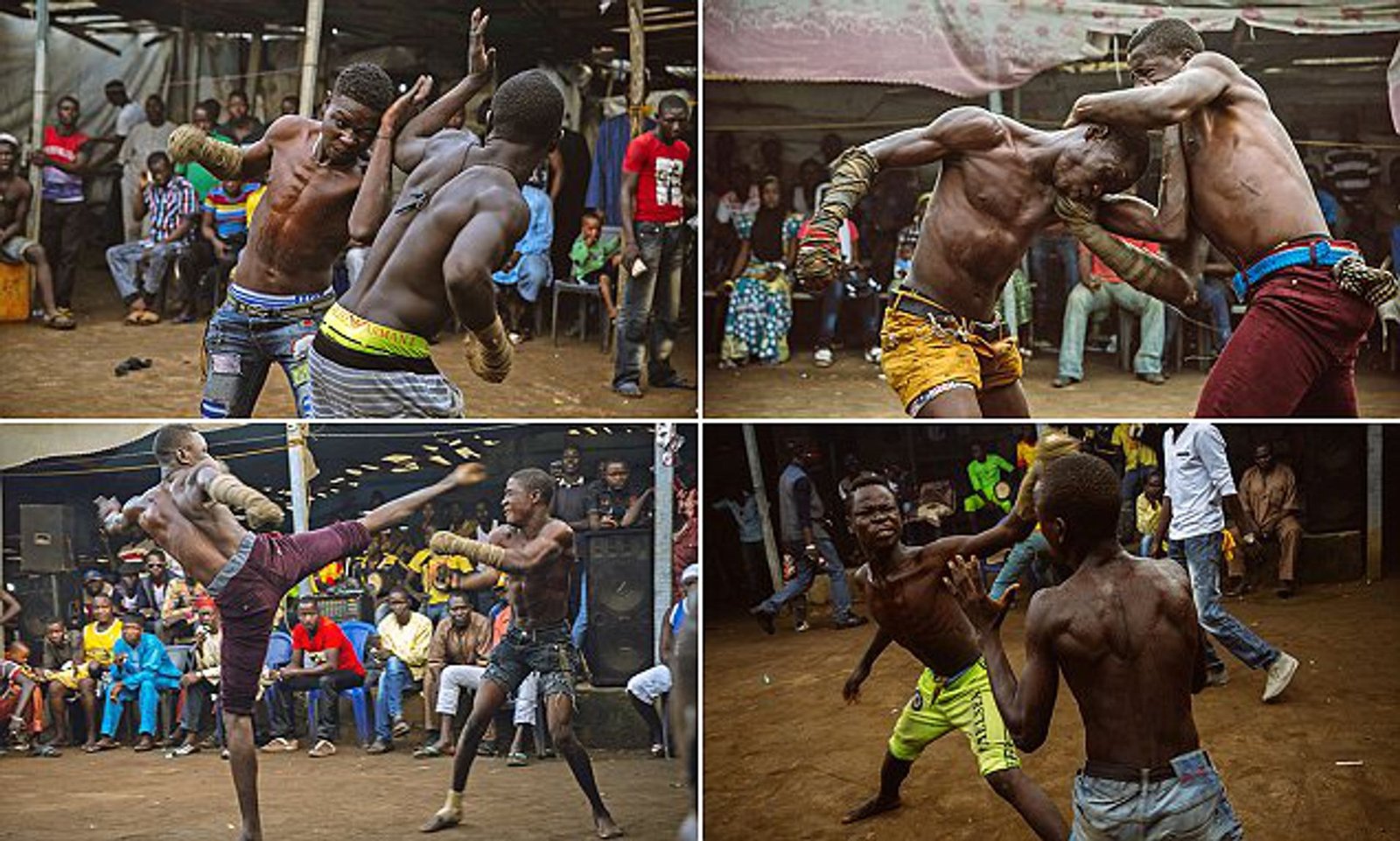

Dambe is a martial art of the Hausa people from Nigeria.[1] Competitors in a typical match aim to subdue each other into total submission mostly within three rounds. It often results in serious bodily injury. Boxers are called by the Hausa word « daæmaænga ».[2]

The tradition is dominated by Hausa fisherman and butcher caste groups,[3] and over the last century evolved from clans of these professions traveling to farm villages at harvest time, integrating a fighting challenge by the outsiders into local harvest festival entertainment. It was also traditionally practiced as a way for men to get ready for war, and many of the techniques and terminology allude to warfare. Today, companies of boxers travel performing outdoor matches accompanied by ceremony and drumming, throughout the traditional Hausa homelands of northern Nigeria, southern Niger and southwestern Chad

The sport has received mainstream attention from Nigeria’s Federal Ministry of Youth and Sports Development as its minister, Sunday Dare pledged in December 2019 to create a national league plus cooperating with the Dambe Sport Association to form a federation for organizing competitions and tournaments across and outside Nigeria,[4] plans were already underway before the COVID-19 pandemic hit the country early 2020.[3]

Techniques

Although there are no formal weight classes, usually competitors in Dambe matches are fairly matched in size.

Matches last three rounds. There is no time limit to these rounds. Instead they end when: 1) there is no activity, 2) one of the participants or an official calls a halt, or 3) a participant’s hand, knee, or body touches the ground. Knocking the opponent down is called killing the opponent.

The primary weapon is the strong-side fist. The strong-side fist, known as the « spear », is wrapped in a piece of cloth covered by tightly knotted cord.[5] Some boxers would dip their spear in sticky resin mixed with bits of broken glass;[6] this, however, became an illegal practice. The other defensive hand, called the « shield »,[5] is held with the open palm facing toward the opponent, said hand can be used to grab or hold as required.

The lead leg is often wrapped in a chain, and the chain-wrapped leg is then used for both offense and defense. The unwrapped back leg can also be used to kick. Because wrestling used to be allowed, and the goal of the game is to cause the opponent to fall down which is referred to as killed and the winner is the person that knocks down the opponent, kicks are more common than they used to be.

Tournaments

Traditionally, contests took place between men of butchers’ guilds who would also challenge men from their village audiences. Drawn from a specific lower caste of Hausa society who were the only ones who could ritually slaughter animals and handle meat, traveling butchers formed boxing teams from their ranks called « armies ». Their bouts took place at festivals marking the end of the harvest season, as clans of butchers would travel to slaughter animals for farm communities. Harvest also marked a time when rural communities were flush with money, so gambling on feats of strength became closely associated with these celebrations.

Today, participants are as often urban youths who train in gyms or backyards, competing year-round. While no longer the preserve of the Hausa butcher caste, the fraternity aspect remains, as youths who join the professional ranks join a professional community which travels to perform bouts in carnival like appearances, complete with amplified sound systems and elaborate pre-match ritual. Side betting for spectators and prize purses for competitors remain an important part of the event.[7][8]

During village bouts, contests take place in a cleared area called the battlefield, with spectators forming the boundaries of the ring. In modern urban bouts, local competitions take place in temporary rings, often setup outside meatpacking plants as members of traditional butcher castes still predominate. In these urban matches, participants wear shorts rather than loincloths. Sand filled West African Lutte Traditionnelle arenas, common in large towns, are used for larger bouts, and are often combined with traditional wrestling championships.

Whether traditional or modern, percussive music and chants precede the bouts. The music and chants are associated with both groups and individuals, and serve to call boxers to the ring, taunt opponents, and encourage audience participation.

In traditional bouts, amulets are often used as forms of supernatural protection.[5] Amulets are seen in modern urban bouts, too, but officials generally discourage the use of magical protection on the grounds of fairness. It is still common that amulets are placed in the feather filled pillows which fighters place in their wrapped fists, and fighters often scar their striking arm, rubbing salves and resins into the healing wounds which are meant to provide strength or defence. Some modern traveling boxing companies engage in ritual smoking of Hemp or Marijuana before bouts.[9][10]

References

- Iyorah, Festus (June 18, 2018). « Dambe: How an ancientian boxing swept the internet ». Al Jazeera. Retrieved June 18, 2018.

- Bole/English wordlist:ucla.edu

UCLA Hausa teaching resources: hausarbaka. - Jump up to:a b Mafua, Juliet (April 12, 2020). « Dambe: The Nigerian combatpirations ».

- AbdulAzeez Bello (December 11, 2019). « Sports ministry to create national league for dambe ». Daily Trust. Archived from the original on 2021-06-10. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

- Jump up to:a b c Rivett-Carnac, Mark (August 12, 2018). « These Boxers Fight With Cords Wrapped Around Their Fists. Crowds Love It ». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

- Boxing in Nigeria: A rumble in the Sahel, by The Economist, dated Nov 18th 2010.

- Traditional Boxing Offers Opportunities for Poor Young Men in Northern Nigeria Archived 2008-11-18 at the Wayback Machine. Sarah Simpson/Voice of America, 19 June 2008.

- Nigeria sports its own style of boxing. AP, Thursday, May 22, 2008.

- VOA: 19 June 2008. BBC: March 2008.

- Green, Thomas A. (2005). « Dambe: Traditional Nigerian Boxing »